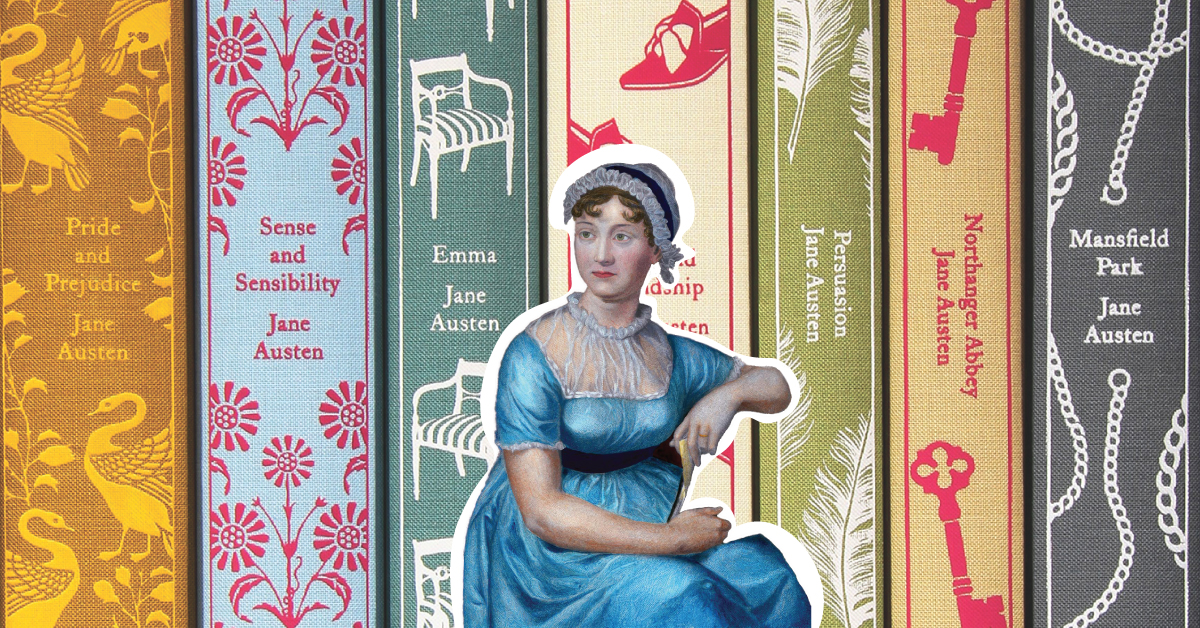

Rebellion & Romance: the Truth About How Jane Austen Made History

I know I’m not the only one whose comfort watch is the 2005 film adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (that Mr. Darcy hand flex? IYKYK). Jane Austen has been one of my favorite authors since I first read Pride and Prejudice at 10 years old. I went so far as to take a class in college that was just about her and her novels. Her wit makes me laugh out loud and her characters ranging from hopeless to reluctant romantics manage to stay relevant even though they were written 200 years ago. But what I find so compelling about Jane Austen is, both in her literature and her personal life, her subversion of the societal norms, especially for women. And in honor of her birthday, let’s take a look back at her life and works.

Her Life

Jane Austen was born on December 16, 1775, in a small village in Hampshire, England. Jane’s letters to her sister Cassandra are the main sources of biographical information that we have on Jane’s life. Her father George Austen came from a line of wealthy wool merchants, but as the years continued, the wealth consolidated, and Austen’s family was forced into poverty.

Although our knowledge about her life is limited, we know that Austen never married or had children. She had romantic feelings for a man named Tom Lefroy when she was 20 and thought he might propose, but since Jane and Tom both didn’t have money, Tom’s family kept the couple apart. Jane never had any other romantic interests as far as we can tell.

Like many other female writers, Jane Austen’s works were published anonymously. Writing as a hobby was fine for a woman, but as a full-time career was seen by society as degrading. With the posthumous publication of her last novel, Persuasion, Austen’s brother Henry included a note that shared Jane’s true identity.

Her Works

Sentimental novels and their offshoot, called domestic or conduct novels, were the popular chick-lit of the 18th century. These novels usually centered on a woman going through a difficult time and this character was contrasted with another woman who was less refined or educated. The idea was to feel bad for the main character and also learn how to (and not) behave.

Jane Austen’s novels critique and satirize the sappy, trite messages, and structure of the sentimental novels. Instead of irresolute girls who are on the hunt for marriage, Austen’s female characters are always just left of what would be expected from contemporary literature.

Lizzy Bennet of Pride and Prejudice knows that everyone around her expects her to marry, but she can’t stop insulting the squirrelly Mr. Collins or getting into disagreements with Mr. Darcy long enough to worry about it. In Sense and Sensibility, one of the main characters, Elinor, is a perfectly polite, genteel young woman – and is foiled by her younger sister Marianne who is headstrong and a hopeless romantic.

Persuasion, one of Austen’s last novels, focuses on Anne Elliot, who is 27 (an old hag by Regency standards) who is still regretting breaking off her engagement with Captain Wentworth eight years earlier. While the novel doesn’t have any big twist (spoiler: she gets back together with Captain Wentworth because he never stopped loving her either), featuring a woman who was more mature was a radical departure for Austen and for her contemporary authors.

Northanger Abbey, Austen’s ode to the Gothic novel, features Catherine Morland as the main character: a young woman who is not particularly beautiful, smart, or wealthy, which would all be features you would expect from a Gothic heroine. Even giving the novel a Gothic overtone, which was out of vogue for literature at the time, shows us that Austen was not afraid to push the boundaries of the tight societal constraints of the Regency England that she lived in.

Her Legacy

Jane Austen lived in a time where society was stricter than it is today. Her novels aren’t completely counterculture; they feature a traditional marriage plot—and let’s not even start on the conversation of diversity (hint: there is none). But that they are adjacent to the mainstream contemporary works is why her novels have endured. They were popular enough in her time to allow Jane to make a living and give her family some financial cushioning, something which would have been difficult for a single woman to do. The stories were similar enough to conduct novels that if you’re not good at perceiving sarcasm, you might believe they were the same.

To satirize in the way that Austen did takes a mastery of the written word and fearlessness to portray women and girls that were not perfect. Female characters that made mistakes and said the wrong things and back talked to their parents. Women that were too old or too loud or too wishful or too pessimistic. For many women and girls, myself included, Austen’s novels are both a comfort and a rallying call. So cheers to you, Jane.

Call to Action

- Check out the Jane Austen Society of North America for more information.

- Support your local bookstores by buying your favorite novel for yourself or to donate to a school or library.

–Sabrina Serani, Content Creator