Spotlight on Nora Ephron: The Queen of Rom-Coms

My bookshelf faces where I sit on the couch and the distinctive robin’s egg blue dust jacket of my Nora Ephron anthology featuring most of her essays, articles, interviews, and the entire script of When Harry Met Sally, stands out from my bookshelf. In times of strife, where some might turn to a religious text or others to the words of a Brené Brown or a Glennon Doyle, I turn to Nora. I take her essays off the shelf or turn on one of her films and the answers that I was searching for come to me in her cadence and voice that is as familiar to me as my own. They say don’t meet your heroes, but it’s to my great sadness that Nora passed away in 2012, the day before my birthday, after a long and private battle with leukemia.

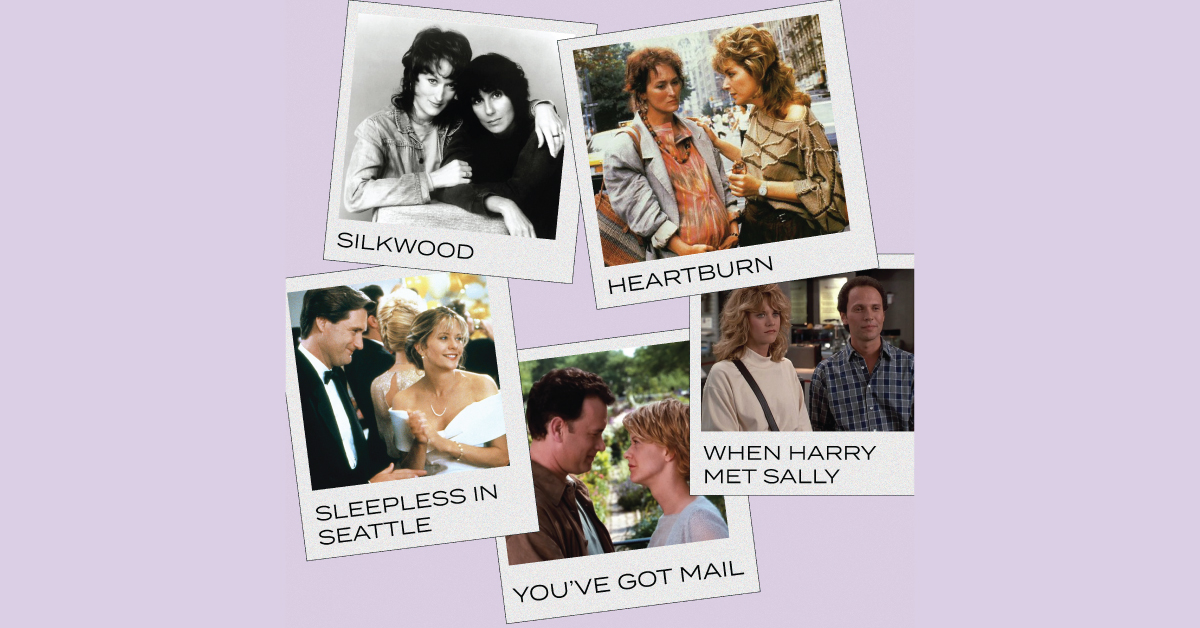

Ephron is still the queen of romcoms — You’ve Got Mail, Sleepless in Seattle, Julie & Julia, and When Harry Met Sally, to name a few — and with Valentine’s Day coming up, it’s the perfect time to reflect on her life and work.

Maybe She’s Born With It

Ephron was born in New York City and raised in Beverly Hills by screenwriter/playwright parents. Nora was the oldest of four sisters and, like their parents, all the Ephron daughters went on to be writers. She attended Wellesley College, a historic women’s institution, and, after graduation, worked as an intern in the White House under JFK. (In one of her essays, she comes forward and claims that she was the only intern JFK never made a pass at.) After lampooning the New York Post’s style in a piece for another magazine, Ephron was hired to work at the Post and broke into journalism. During this time, she moved back to New York City, which would become the backdrop for some of her films and cement her identity as a New York icon.

Ephron continued to write for print publications. Her break into screenwriting came when she rewrote a script for All the President’s Men, the political biographical drama about the Watergate scandal, with her then-boyfriend and eventual ex-husband Carl Bernstein (of Woodward and Bernstein). When her script wasn’t accepted, she was offered another job to write a television movie and her screenwriting career took off from there.

“Four Careers and Three Husbands”

Ephron’s trajectory was uncommon for her peers — notably because she pursued a career in a time when women weren’t expected to do much of anything except to be housewives and homemakers. In her commencement address at Wellesley College in 1996, Ephron said, “We weren’t meant to have futures, we were meant to marry them.” Ephron also wasn’t afraid of being considered a failure or wanting to do something different: “…you can always change your mind. I know: I’ve had four careers and three husbands.”

“Everything is Copy”

Ephron’s mother imbued her with the piece of advice that would guide her career: everything is copy. Everything and anything that happens to you is fair game to write about. As long as you continue to live, you will always have inspiration.

Like the semi-autobiographical Heartburn, based on the dissolution of her marriage with Bernstein, or Julie & Julia, which was Ephron’s own love letter to food framed in the stories of Julia Child and Julie Powell, Ephron’s works are smart, funny, and relatable. When she was younger, she dreamt of being the next Dorothy Parker: a successful poet, writer, critic, and satirist. What Ephron became is something all her own: a writer and director who told stories of the human condition that confronted things like aging and mortality through the frame of something as innocuous as a rom-com or a blog post.

Ephron was labeled a practitioner of New Journalism, a style nascent in the 1970s that used literary techniques in news stories, but Ephron eschewed the label. “I just sit here at the typewriter and bang away at the old forms.” If there was any philosophy that Ephron subscribed to, it was to make life more fun and to pave roads for women where there weren’t any previously. “I try to write parts for women that are as complicated and interesting as women actually are.”

Ephron isn’t a classic ideal of second-wave feminism. She bemoans the physical side of aging, most famously in her collection of essays, I Feel Bad About My Neck. She called out Betty Friedan for starting a feud with Gloria Steinem. But Ephron illustrates the realistic, attainable aspect of the pursuit of feminism. Ephron’s ethos, if it could be summed up into one quote, would be this one that lives on a sticky note above my desk, battered and rewritten every few months: “Above all, be the heroine of your life, not the victim.”

Call To Action

Watch one of Ephron’s many feel-good films or go out of your comfort zone and watch one of the winners of the Tribeca Film Festival’s Nora Ephron Prize. The $25,000 goes to a female writer or director with a distinctive voice. Past winners include Asia, written and directed by Ruthy Pribar and starring Shira Haas from Netflix’s Unorthodox, and Little Woods, directed by Nia DaCosta and starring Tessa Thompson. (DaCosta is directing the upcoming Candyman sequel produced by Jordan Peele and the sequel to Captain Marvel.)

Support your local independent bookstore and pick up or ask them to order one of Ephron’s books.

–Sabrina Serani, Content Creator